Simone Weil, Calvinist?

I’ve recently been wondering whether my devotion1 to SIMONE can be ascribed to the fact that she offered me a perennialist spin on the Calvinist convictions that I, despite everything, still appear to hold.2 I am, by second nature, an iconoclast. Through bitter experience, I’ve come to learn that this is not always a good thing. SIMONE’s most toxic trait — and the one most likely to appeal to contemporary audiences — is her Manicheanism.

Nevertheless, I’m against attempts to deradicalise SIMONE and reduce her to an array of inspirational quotes, like the one from everybody’s favourite settler-colonialist A.C. that floated past in my Notes feed just now: “In such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, not to be on the side of the executioners.” (i.e. the more self-flattering version of “Between justice and my mother, I choose my mother”, which he had also said). In contrast, SIMONE does not believe in sparing the rod — and not in a campy S.C.3 kinda way:4

In a relationship of very unequal strengths, the stronger can be just toward the weak either by doing them good with justice, or in doing them harm with justice. In the first case, there is charity and in the second case, there is chastisement.

Just chastisement, like just charity, includes the real presence of God and constitutes something like a sacrament. This also is indicated clearly in the Gospel. It is expressed in the words, 'He who is without sin, throw the first stone at her.' Christ alone is without sin.

SIMONE isn’t always right, but she makes for a fruitful interlocutor precisely because of her stubbornness: she refuses to accept any spiritual authority beyond her own and that of God, who is absent, yet secretly present, "here below”. Although she mostly writes as if Catholicism is the only legitimate form of Christianity, she reads the Bible as thoroughly as any Protestant. Here she is writing to a priest about the imprecise Latin translation of the first verse of that most mystical of the canonical gospels, the Gospel of John:

The very fact that we have translated λόγος (Greek) as "verbum” (Latin = Word) indicates that something has been lost, for λόγος means above all 'relation' and is synonymous with αριθμός (number) in Plato and the Pythagoreans. Relation, which is to say proportion. Proportion, which is to say harmony.

Harmony, which is to say mediation. I would translate it, 'In the beginning was Mediation.’

WORDS ARE VERY UNNECESSARY

I enjoyed reading STOP ALL THE CLOCKS: A NOVEL by NOAH KUMIN. The themes of A.I., the value of literature and the future of humanity couldn’t be more à propos. It might not have been as much fun as reading THE DA VINCI CODE: A NOVEL by DAN BROWN but the characters were more rounded. I do have to say, though, that I had hoped that NOAH KUMIN’s close association with the weird nexus between reactionary politics and I.T.5 would have enabled him to shed some fresh light on these matters. But alas, few of the ideas in this “rare literary thriller” struck me as as all that, well, NOVEL.6 The biggest idea that I could spot was that it would be a darn shame if we let I.T. extinguish our souls. If I wanted to be a bitch,7 I could have said that without the dose of MYSTICISM, this NOVEL could have been a SPOKEN WORD PERFORMANCE by the GEN Z poet KORIJANES, a disciple of JONATHAN HAIDT.8 But I won’t be a bitch (see the end of footnote 5).

My biggest difficulty with getting into groove of this NOVEL was accepting the premise that an A.I. engine could learn to get POETRY in a way that most people just don’t and that this understanding would enable it not only to write human-grade POETRY but to manipulate REALITY in a way that would excite a transhumanist tech mogul. Maybe I’m just too old and jaded to be the target audience. I’m no longer hoping to discover some authentic esoteric tradition hidden away from the mass of believers and unbelievers, with the secrets of the universe revealed only to true initiates. I’m especially sceptical that this can be achieved through POETRY alone. Take the following statement by the main character, quoted by T.D.-S. in his rave review:

If you ask me, all language is a just a lonesome prayer that we and the world actually exist, a cry in the wilderness to the god of meaning. And, miraculously, that god hears us. When I say ‘The sky is blue,’ it’s a miracle that you have any sense at all of what I’m saying. It’s a miracle that I can induce a feeling in other humans with this series of abstract grunts and yawps and plosives. We almost never stop to think just how strange language is, how poetic and potent and recondite and prayerful just to say ‘The sky is blue!’ The possibilities are limitless. Someday a great poet may write an epic in which everything hinges on that single line!”

It’s true that human language enables abstract thinking, but that hardly makes it miraculous in a way that the communication between between flowers and insects or between tree roots and mycelium is not. A blind person can develop a theoretical understanding of the phrase “The sky is blue!” but can such an understanding be compared to the experience of looking up at the heavens?9

As an analogy for the very substance of reality, mathematics would seem a more robust choice than language. But maths is hard,10 so it is hardly surprising that the average English major on shrooms would vibe more with the “everything is language” squawking of Tao Lin’s mentor T.Mc.K.11 Computer programmers are tempted to think of the world as a simulation coded by God; manipulators of language are primed to think of God as speaking the world into existence.

In MGM, the Anglo-Irish-British IRIS is quite scathing about the deconstructionists in general and about Jacques Derrida in particular:

We may be quite prepared to be told that there is no God, that we are limited contingent beings affected by forces beyond our control, and that 'language' (now studied by scientific experts) is a huge area of which we know little. All this may seem obvious, easily put up with, part of living in this age. We then find that further steps have been taken which purport to deny our ordinary sense of a transcendent (extra-linguistic) real world 'out there'; indeed there is no 'out there' since language, not world, transcends us, we are 'made by language’, and are not the free independent ordinary individuals we imagined we were. This alarming mystification gains some of its plausibility from moves, critical of traditional concepts of 'self' and 'mind’, effected by (for instance) Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Sartre, Ryle and others. How far do these moves take us in the direction of finding that the 'individual' with his boasted 'inner life' is really some kind of illusion? Are not these moves just 'technical', inside philosophy, not to do with us? Perhaps philosophers were influential in the past, but now we think more scientifically. Is it just that 'the elimination of the self' is in the air, have we not been prepared for it by Marx and Freud? Does it matter? Wittgenstein says that (his) philosophy leaves everything as it is; whereas Sartre and Heidegger are by contrast prophets who want to change our picture of the world. Derrida (who is not strictly a Philosopher) seems to have been, after all, by imparting his doctrine to literary writers and critics, the most generally influential.

IRIS on T.S.E. on liberalism as Romanticism

In light of the ongoing hopes of a Romantic/Modernist/Anything-but-this! revival, I reread IRIS’s contribution to the 1958 Symposium for T.S. Eliot’s 70th birthday, in which she provides a lively summary of his thoughts on “liberalism”:

Mr. Eliot sees liberalism as the end product of a line of thought which is to be found in Stoicism, in the Renaissance, in Puritanism, in the Romantic movement and in nineteeth-century humanism. Characteristic of this line of thought is a cult of personality and a denial of authority external to the individual. In the fissure between Dante and Shakespeare lies the loss which Mr Eliot mourns; the self-dramatization of Shakespeare’s heroes foreshadows the romanticism of the modern world. The Puritans continued more insidiously to undermine tradition and authority, and with their thin mythology inaugurate the age of amateur religions. Authorised by Kant, inspired by Blake, and more recently encouraged by Huxley, Russell, Wells and others, every man may now invent his own religion, an have the pleasures of religious emotion without the burden of obedience or dogma.

The post-libs (P.D., A.V., S.A., R.D etc.) have added little to the basic critique:

Romanticism, that debilitated Renaissance, with its denial of original sin and its doctrine of human perfectibility, attacking an organism weakened already by the Puritans, produces the new style of emotional individualism; and humanism, in an attempt at remedy, confounds the categories even further by offering a high-minded version of that confusion of art with religion which with the Romantics had at least remained at a more orgiastic level. So, out of Matthew Arnold, out of the 'dream world' of late romantic poetry, out of the mid-nineteenth century, that 'age of progressive degradation,' issues liberalism, the imprecise philosophy of a society of materialistic and irresponsible individuals.

It’s easy enough to trace the road from “emotional individualism” to limbic capitalism. T.S.E. is rather prophetic about the consequences of liberalism, although the “historical reality” he wishes to use as bulwark appears risible in hindsight:

Liberalism is a creed which dissipates and relaxes; and it prepares the way for that which is its own negation: the artificial mechanized or brutalized control which is a desperate remedy from chaos. We have the choice of a society bound for the extremes of paganism, or a society more positively Christian than our own. Mr Eliot turns to appeal, over the head of the dominant creed of the time, to an older, purer tradition.

The historical reality upon which he relies is the Anglican Church, the only instrument through which the conversion of England can be achieved; and he pictures: a Christian society, inspired by a Christian élite, and reminded by the Church of standards which lie beyond the individual.

Some believe that in the Year of Our Lord Twenty-Twenty-Five, only something called “the left” can supply these “standards which lie beyond the individual”. But maintaining such standards will require more than language games.

There are two approaches to philosophy and art: that of devotion and that of conquest.

I appreciated

‘s rigorous essay on the young J.M. Coetzee’s “Calvinist fiction”, especially the way K.L.T. was able to sketch the background to Afrikaner Calvinism much better than I could have (maybe lived experience doesn’t count for everything?):Calvinist also applies because Calvinism underlies Coetzee’s upbringing in the white South African Afrikaner community which descended from the Dutch Calvinist Boers. These warlike farmers captured and colonized inhabited South African lands in a heretical, too-literal imitation of the Hebrews expelling Canaanites and other heathens to possess the fertile lands which God had promised them. The new covenant of Christ, to make disciples by faith of every nation and baptize them into Christian glory, was apparently too modern for their territorial interests. The Reformed Church in South Africa separated from the Dutch Reformed Church in the Netherlands in 1824, likely over the Dutch plans to increase the missionary work of converting the natives (rather than the Boers’ preferred work of subjugating them). The Boers feared the gelykstelling of such missions, the “equalization” of blacks and whites under God. Their sinful fear for some unbiblical racial purity eventually became the Boer Reformed churches’ support for the apartheid regime for nearly its entire existence.

After my conversation with D.O., K.L.T. also kindly pointed me to J.M.C.’s diary entry about his growing ambivalence towards the language he had long professed. I held out longer than J.M.C. against the linguistic colonialism of my mind: I even wrote my university exams in Afrikaans. (My voorname is nader aan Johannes Machiel as John Maxwell: my biologiese herkoms is meer verkrampt as verlig.)

But when I speak the Imperial tongue, I make sure I don’t sound like a Boer.

I’m threatening to write a post called The Paglia Question: Ladies, do you want to be a princess or a drag queen? because those of the X.X. persuasion are giving me mixed signals. If post-woke means the return of the 2010 online sex wars (as 3/4ths of my recent Substack feed suggests), then please unalive me now.

From “Forms of the Implicit Love of God” in Awaiting God, translation by Bradley Jersak.

N.K. would appear to have a steeper climb back to respectability than M.G., who can claim to merely have documented the fash-curious scene from the sidelines, rather than sharing an URBIT constellation with the Dark Lord M. M. But maybe we’re not doing the guilt-by-association thing anymore…

Since it has become customary to drag out the skeletons from our intellectual closets and ceremonially display them in a ritual of mass penance for what we have become, I will confess that I did at one time, during a particularly dark period of my life, read M.M.’s output with some enthusiasm, although, not unlike some of my readers, I much prefer the prosody of N.L.’s Dark Enlightenment. These writers never “radicalised” me — they simply provided a good old-fashioned guilty pleasure. Like with other forms of PORN, I have since found more refined ways of indulging my shameful urges. (Rest assured: there is no archive of off-colour jokes posted under a different pseudonym — I was only ever less than fully anti-racist in my heart.)

After The Mars Review of Books consciously uncoupled from URBIT and re-entered the normiesphere here in Substackville, I became a paid subscriber to read J.P.’s dual review of H.L.’s My First Book and M.C.’s Earth Angel (Putting the ‘It’ in 'It’ Girl) (read J.P.’s NON-REVIEW of STOP ALL THE CLOCKS: A NOVEL by NOAH KUMIN here). I remain a subscriber mostly because it would feel awkward to suddenly unsubscribe, especially since The Mars Review of Books seems like the kind of venue that might be interested in publishing a somewhat problematic neurodivergent drug nerd like me. (As part of his Delusions of Grandeur exhibition at the W.C. — which I wrote about here — G.P. quoted N.J.P: “An artist's job is to bite the hand that feeds him, but not too hard”.)

I don’t want to be too hard on N.K., since the problem is systemic. Like racism, but worse. If the world did indeed, in any objective sense, end at 23:59 12/12/1999 (give or take a few decades), as I was reliably informed (in a vision), it might explain a few things, i.e. how nothing "new" (i.e. not anticipated by a 90s movie or land war) has happened in the last quarter-century.

Yes, of course I’m envious those who can say: I’m not a bad guy. I wrote a novel!

F.d.B. writes that what writers give their readers is permission. IRIS has given me permission to admit to my own spiritual mediocrity. Logically speaking, there is no reason why I of all people would have been blessed with an extra helping of goodness. But it was nevertheless a particularly difficult truth to make peace with. So now I’m trying to make sense of IRIS’s statement that the concept of Grace can easily be secularised.

Who said Substack wasn’t cool?

The book’s title is from the first line of W.H. Auden’s Funeral Blues — a poem that uses very simple language to expresses the unfathomabilty of grief.

Alan Jacobs has been writing a lot about W.H.A recently. When Alasdair MacIntyre died, he reflected:

MacIntyre’s work helped me to understand the ways that Auden’s poetry in the Forties and Fifties anticipated movements later to become important. Auden’s anti-Constantinianism, his theology of the body, his communitarianism, all of them were ahead of the game, and MacIntyre helped me to understand the ways that Auden was both participating in and helping to form a “tradition of moral inquiry.”

In his subsequent post, A.J. reflects on When Auden was wrong and links to his introduction to W.H.A.’s The Age of Anxiety, which I can recommend even to those who, like me, have no intention of reading the book-length poem any time soon. (I’d guess that the spiritual benefit from modernist poetry arises from the focus and discipline required to make sense of it, but that is just a hunch — ask

who actually reads the stuff!)Although SIMONE beat De Beauvoir at philosophy at university, she always felt intellectually inferior to her brother the mathematician.

For the record, the shrooms have always told me the opposite: that what really matters can only very imperfectly be put into words.

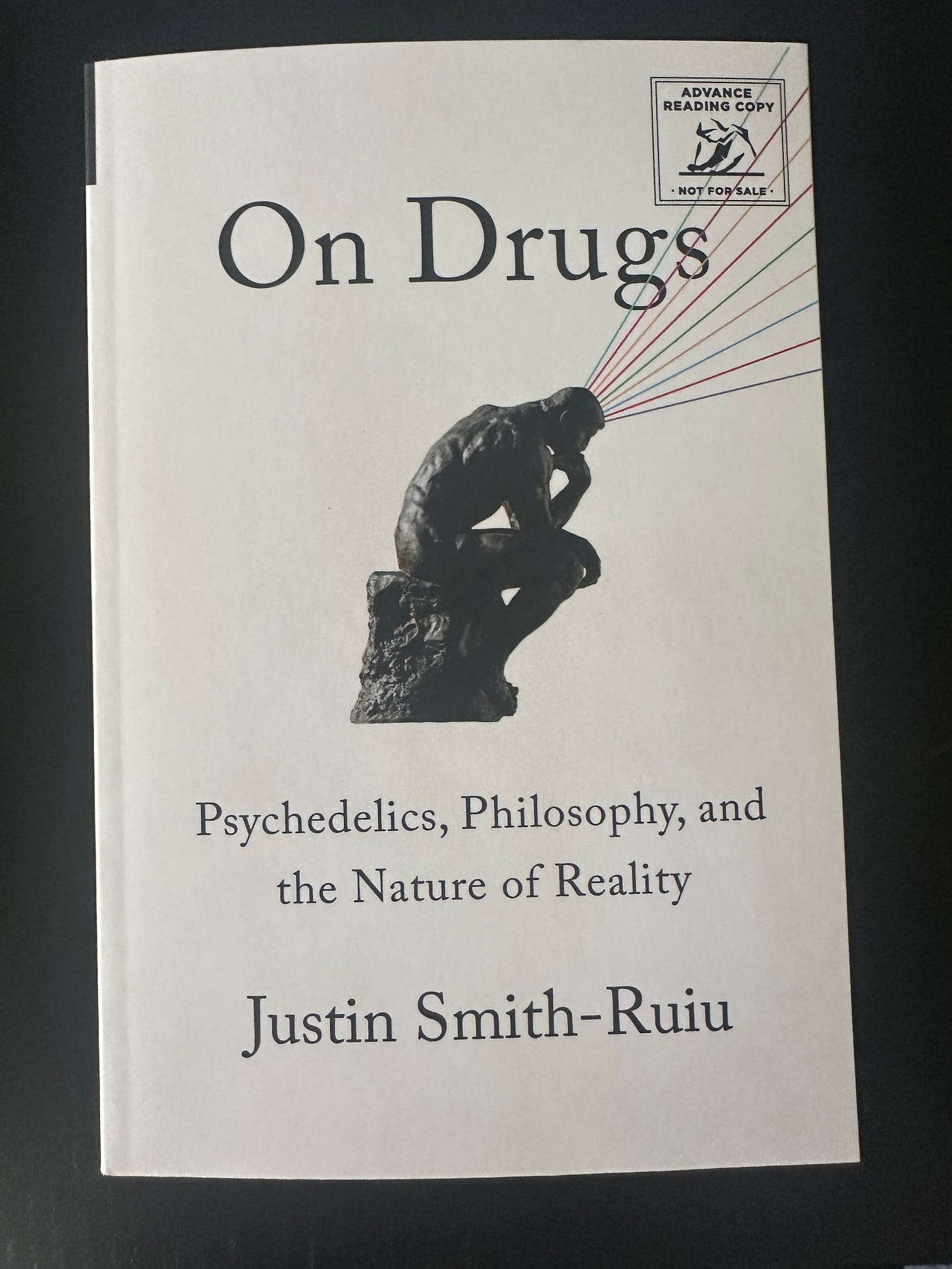

Speaking about drugs, it turned out to be much harder to get my hands on an A.R.C. of On Drugs than on actual drugs (no fault of J.S-R. who has been very gracious throughout the procurement process).

From the little I’ve read so far, it seems that J.S.-R. and I are broadly aligned in our views on drugs (psychedelic and otherwise [although, despite my Huguenot heritage, I’ve fortunately never been bound to the vine]), so I’m curious to see whether he will challenge me to rethink any of my views on philosophy and the nature of reality.

Drug nerd that I am, my red pencil came out on page 1 to circle the “seeds” for sale in the Dutch smartshop: “Spores!” I wrote: “Mushrooms propagate via spores! Respect the Fungus!!” I was however surprised to learn that the word “drug” comes from the Dutch word “droog” (dry) referring to herbs, back in the days of the spice trade. (Toe die Kaap nog Hollands was). Nowadays the Dutch use the English word drugs for drugs, whereas in Afrikaans we say dwelms, derived from an Old Dutch word for delirium.

If there are any counterhegemonic publications who would be interested in publishing my eventual review of On Drugs, my D.M.s, like my mind, are open!

If "Stop All the Clocks" is the sort of novel that leads you to consider reality as either poetry or mathematics, then I'm for sure going to have to read it. It was already on my list, but the persisting "Chesterton" and "thriller" comments have made me a little wary (I like my novels like I like my morning sky - slightly moony, without much motion). I have also been curious about the technical underpinnings it might have, as I continue to approach (be sucked into?) attempting to understand new and past technologies more concretely.

I look forward to wherever your review of "On Drugs" eventually appears!

I prefer to cite the things chatacters in Terry Giilliam films say'no' to precisely as Romantic. And our working definition for the ism will be a clutch of synopses of Gilliam movies redacted with a black marker for clarity.