I’ve been haunted by the opening paragraph of this blog post by the indispensable Alan Jacobs:

I used to call my blog Snakes & Ladders, because that reflected my belief that culture – culture-as-a-whole – is never simply ascending or declining, but is undergoing in its various locations constant ups and downs. But beneath that point is an image of myself as an observer and critic of this cultural moment. Now I call the blog The Homebound Symphony, in honor of the Traveling Symphony in Emily St. John Mandel’s novel Station Eleven, because I have stopped thinking of myself as an observer and critic and started thinking of myself as a preserver and transmitter. Another way to put this: Whereas I once tried to be a public intellectual, I now just want to be a … I dunno, maybe a convivial conservator.

And seeing as I’ve been trying (and largely failing) through the writing of this blog to direct energy outwards, away from my fat relentless ego, I thought it might be worth attempting to convivially conserve some of my troubled Afrikaner heritage.1

Starting off nice and easy with an uncharacteristically sweet and simple love poem2 by the Afrikaans poet Breyten Breytenbach, written for his Vietnamese wife while he was in the Pretoria maximum security prison serving a sentence for high treason against the Apartheid government.

The audio is me reading the poem in Afrikaans and I’ve translated it into English below.

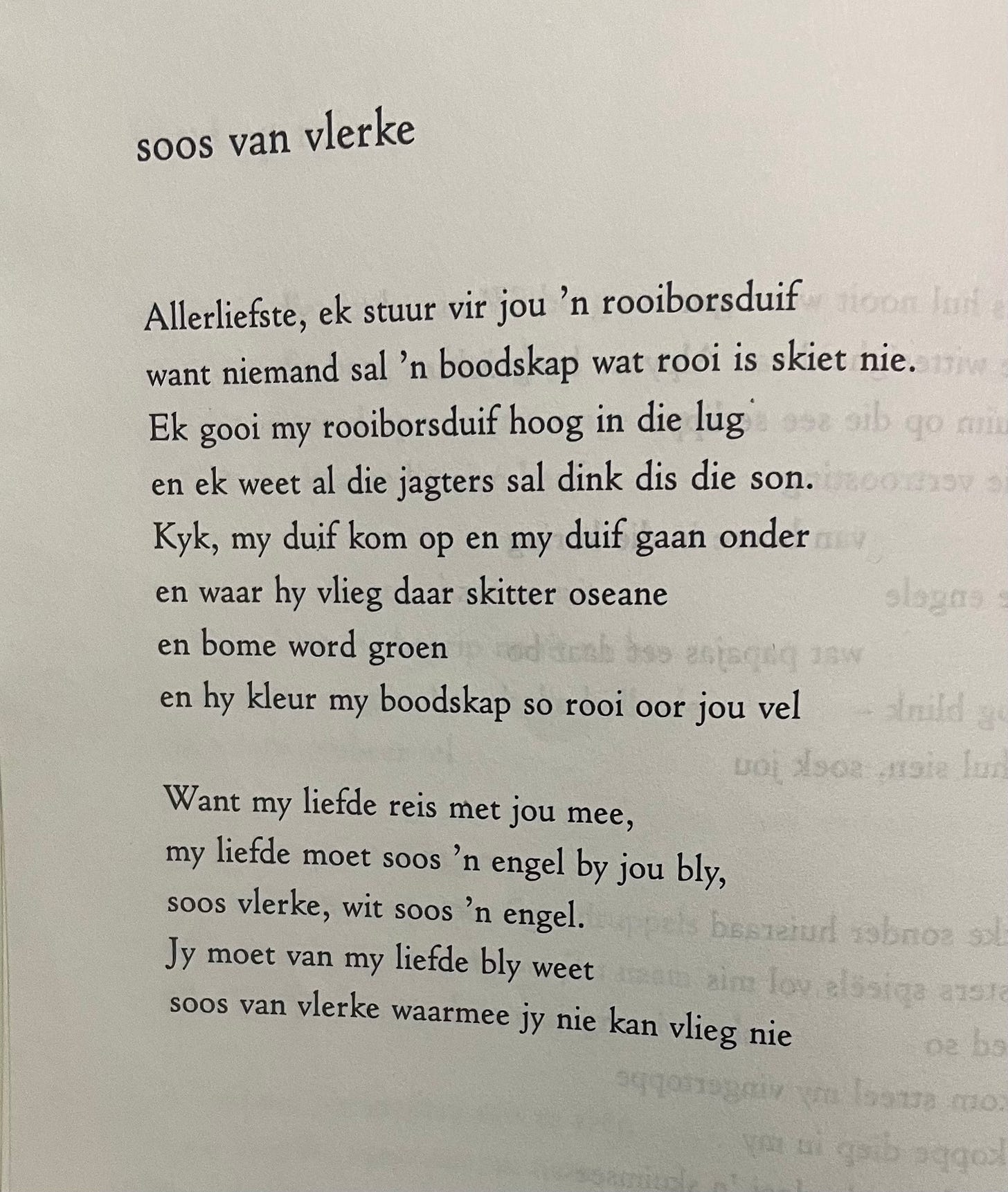

like with wings

Most beloved, I’m sending you a red-breasted dove3

because no-one will shoot a message that is red.

I launch my red-breasted dove high up in the air

and I know all the hunters will think it’s the sun.

Look, my dove rises and my dove goes down

and where he flies there oceans glitter

and trees become green

and he colours my message so red on your skin

Because my love travels with you,

my love must, like an angel, stay with you

like wings, white like an angel.

You must keep knowing of my love

like with wings with which you cannot fly

I’ve also been haunted by what John Pistelli wrote about the distinction between non-Anglo-Anglos and pure Anglos being more important than racial distinctions (I can’t find it but I’m sure he can provide a link in the comments) so also see this project as a potential enrichment of the Anglo literary bloodstream.

Dedicated, of course, to my long-suffering gen z boyfriend (who has graciously admitted that he had overreacted about the twink).

Rooiborsduif is one of the Afrikaans names for Spilopelia senegalensis pictured above (the other is lemoenduif, lemoen being Afrikaans for the fruit that in English is called orange — whereas what the English call lemon we call suurlemoen, literally a sour orange). I’ve translated the word literally rather than use the standard English name (laughing dove), because red is a powerful symbol in the poem.

Beautiful translation

Thank you for sharing this! I am not fluent in Afrikaans, but my feeling is that English doesn't do it justice (as with any language, I'm sure). Despite this, I found the experience of reading your translation of the poem to be quite moving! I've always appreciated how descriptive Afrikaans is -- 'skitter' says so much more than 'glitter' does, doesn't it? (My favourite word is 'tarentaal'). Great to get a glimpse into the decision-making involved in translating! I'd love to read more of your translations!