John Pistelli’s serialised-on-Substack novel opens with what Camus called the only truly serious philosophical question.12 A male student in an oversized army jacket shoots himself in the head with a vintage revolver; a classmate films the incident and whispers Quod Erat Demonstrandum.

This major (but by no means arcane) novel is Pistelli’s own attempt at a Q.E.D. of the proposition that, despite the anaemic state of officially sanctioned contemporary literature, one can write imaginatively about the present.3 In my opinion, the proof succeeds.

Major Arcana celebrates artifice while abjuring obscurantism (for the midwits among us, Pistelli tells us exactly what he is up to4 by including both a Preface and a Foreword to the Preface of the Proem of the Novel of the Future5 and by providing running commentary on Substack and Tumblr). He makes full use of the serialised format: each chapter, evocatively titled and carefully bounded, can be savoured on its own, perhaps even shuffled at random (especially in its audio form, as the author doubles as a gifted voice over artist).6 The ethics of the novel similarly evokes an earlier model of la littérature engagée with its richly inventive backstories for characters that could otherwise have been simple mouthpieces for this or that theory of art and the unsparing attention paid to the not-always-creative destruction wrought by technological and cultural change.

Concurrently, the boundaries of the novel, like that of the soul, are porous: events from cyberspace seep into the story and one has the sneaky suspicion that the occult forces that have been summoned may already have escaped into consensus reality. Unlike other “Internet novels”, this book (or whatever) doesn’t simply wallow in the anomie and anhedonia that predictively results from shackling oneself to a particular hellsite, lol,7 but swallows the Internet whole, with room to spare for the world before it, and God willing, the world thereafter.

After the climactic opening sequence,8 we are slowly introduced to a colourful suite of characters to explain (or fail to explain) why Jacob Morrow, that beautiful boy, decided to sacrifice himself; and why Ash del Greco, that weird-looking girl (or whatever) with the spiral scar on her face, decided to film the scene to prove a point.

First up, in a brief but hilarious satire of 21st century campus life, we meet the self-mythologizing Simon Magnus, former countercultural comic book author and current adjunct lecturer of Studies in the Graphic Novel, who gave up writing comics, gave up writing anything really, after the bloody genesis of Simon Magnus’s magnum opus Overman 3000.

One half expects Simon Magnus to start a YouTube channel destroying the arguments of the insufferable enbies in Simon Magnus’s classroom in a building that is literally called “the Cathedral”9 but instead Simon Magnus decides to beat they/them at they/their own game and destroy the very idea of gender identity through a reductio ad absurdum by first suggesting that everyone should be referred to as they/them regardless of personal preference before insisting that, actually, now that Simon Magnus thinks about it, Simon Magnus would prefer not to be referred to by any pronouns at all — a request which the narrator scrupulously honours, effectively illustrating how the necessary hubris of the artist is often difficult to distinguish from the male sense of entitlement to act like a dick. But the administrative empire strikes back, placing Simon Magnus on leave pending an investigation by the sinisterly named non-profit Community Harvest into possible trigger points in Simon Magnus’s oeuvre that might have contributed to Simon Magnus’s student’s self-harm or self-slaughter (or whatever we are now supposed to call suicide).

The tone shifts abruptly but effectively from comic to tragic as Jessica Morrow, our first lady of sorrows, looks back on her life in a hopeless attempt to understand why she, who had tried so hard to be the loving and nurturing parent that she had never had, had nevertheless failed in her basic responsibility of keeping her beloved Jakey alive. Then follow several other stories of characters trying to escape lonely childhoods and broken homes through literature and art (and other less wholesome means), with the most harrowing of all being that of Valerie Karns, reaching such Dostoevskyian depths that one can’t help but wonder whether Pistelli is of the devil’s party without knowing it.10

In Simon Magnus’s retelling of Simon Magnus’s personal myth, however, Valerie Karns is reduced to “the mysterious figure who had initiated Simon Magnus into the mystery before disappearing into it herself”.11 It is Valerie Karns who introduces Simon Magnus to the tarot and to magic and to Aleister Crowley with his motto of “Love is the law, love under will”, of which she will retain only the first clause in her final red message. In the novel, magic possesses a certain (dare I say capitalist) efficiency: you may very likely get what (you think) you want, but it comes at a cost.12

If this makes the novel sound like a quantum entanglement of trauma plots, fear not. It explores not only the depths but also the breadths and heights of human experience. Neither biology nor sociology is taken as destiny. Words and images have the power to trap the characters but also to set them free. Conversations, even arguments, are sources of entertainment and instruction. Take for example the following exchange between Simon Magnus’s lover, a lapsed Catholic aesthete, and Simon Magnus’s visual artist collaborator on Overman 3000, a Stalinist Jew:

“I was raised Catholic,” she said to him one night in the bar after a moment’s silence. “The whole fucking religion is a graven image. That’s the only good thing about it! Otherwise, it’s old men in dresses telling you not to have any fun while they eye up the altar boys. The sermons would put you to sleep, but you could always stay awake by looking at the stained glass windows—the way they colored the light that came through them and spangled the backs of the people in the pew in front of you—and those sadomasochistic reliefs of the Stations of the Cross on the wall, all that flogging and bleeding of the beautiful male body, like something out of Mishima.”

Her eyes glassed over in reverie as she dragged on her cigarette.

“Well, there you go,” he said. He raised his beer glass and slammed it down to re-seize her attention, rattling the fruity wine in her flute. “You were missing the parables, the allegories, the commandments—distracted by some goddamn sex fantasy.”

Pistelli’s keen sense of humour prevents the narrative from ever descending into mere didacticism, but something of the Invisible College lecturer nevertheless shines through: attempting to convey not facts or arguments, but sensibilities — ways of seeing, if you will. Perhaps the most important lesson is the ability to read the world as fiction, which is not to say that the outside world doesn’t exist, but that there is a lot more to the real than the unimaginative mind is capable of perceiving. Wittgenstein said: “The world of the happy man is a different one from that of the unhappy man.” Or, as Ash del Greco, in her incarnation as virtual manifestation coach, told her customers:

If you change the way you think about the past so radically that it changes the effect the past has on you—how is that not magic?

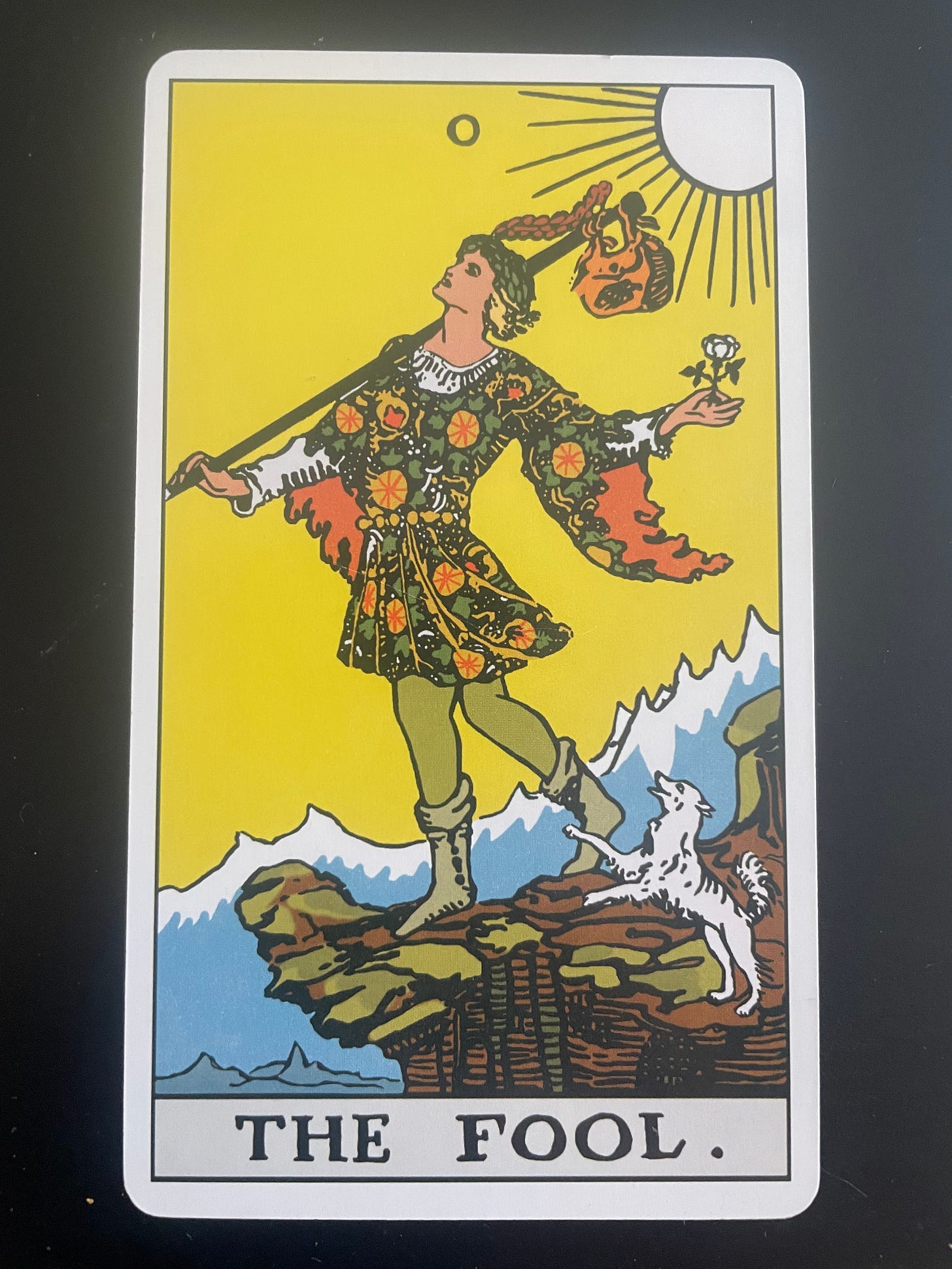

The transparent refictionalisation of existing fictional characters (Overman, Ratman, The Fool, Sparrow, Marsh Man) reveals the archetypal nature of the overfamiliar brands and franchises which have become dead metaphors.13 Nevertheless, one does not have to be a fan of comic books to enjoy the narrative.14 In Simon Magnus’s youthful musings about the proper relationship between tradition and innovation, you could replace ‘comics’ with any popular art form:

Alone, Simon Magnus might have found the comics too simplistic and banal to hold much attention and the classics too antique and convoluted to move the body and the soul. Together, however, the one set of books fertilized the other. Simon Magnus felt through the comics’ crude images something of the passion and despair Milton, Shelley, and Dostoevsky meant to convey, while discovering at the same time, through the classics’ elevated diction and thematic grandeur, the ideals those superheroes manifested for a popular audience in the present.

After the fateful quickening of Overman 3000, and of Ash del Greco, we return to the present, more or less. The skewering of gender pieties, language policing and Covid protocols are familiar, although of course we’re used to seeing it from pseudonymous chaos magicians, rabid right-wingers and reactionary centrists, rather than intellectually and morally serious writers whose aims transcend the political.15

Pistelli is not attempting to redpill his audience — nor to blackpill them or pinkpill them or to feed them whatever pill the cool kids are taking these days. In fact, in our pharmacotopian era, he dares to suggest that ingesting a chemical (government issued or otherwise) may not be the most advisable route to true insight. I’d go further, though, and call the novel’s guiding ethos anti-enlightenment: if by enlightenment is meant a binary transition from illusion to reality, from dreaming to wakefulness, from darkness to light.

The novel’s (non)duality is most clearly illustrated by the parallel gender journeys of Ash del Greco and her high school friend Ari Alterhaus. Ari Alterhaus attempted (with enthusiastic parental support) to literally excise the gendered aspects of their anatomy by means of hormones and surgery only to end up as a Catholic convert and detransitioner. For Ash del Greco, however, dysphoria about her (or whatever) gendered body was but a small part of her general dissatisfaction with her corporal existence, which she quickly realised could not be assuaged by dictating how others should refer to her in the third person. Having already undergone much more fundamental transformations, she foresees:

She would never detransition because she would never cease to transition. Her whole life was nothing but transition.

A hostile reader could question why, in the current political climate, Pistelli chose to make this point by bringing to life the fever dreams of the likes of Wesley Yang and Mary Harrington, when other examples of techgnosis abound. But in his artful response to cultural developments that have evidently deranged many otherwise intelligent observers, Pistelli offers an alternative to both leftwing and rightwing censoriousness. We would all be wise to heed this lesson, since the 21st century isn’t likely to become any less weird.

Contra Crowley and the young Simon Magnus,16 the narrative suggests that we do not need to push ourselves to ever further extremes to find the truth, that there may yet lie great wisdom in the pragmatic pluralism of William James: a willingness to give a fair hearing to both missionaries and visionaries, to prophets and perverts and freaks, without renouncing the ordinary (dare I say bourgeois) delights offered by friendships, old books, babies and dogs.1718

The novel communicates a vision of life as a deck of cards, endlessly shuffled and reshuffled: the same images occurring again and again in different combinations. In the end, though, it is not the surprising correspondences cooked up by chance and fate that bring meaning to successive readings, but the growing ability of the reader to notice the patterns unfold.

24/07/24: I replaced the AI generated image that originally accompanied this post with a photo of The Fool card in the Waite/Smith tarot deck.

Disclaimer: I don’t know John personally, but he has been exceedingly generous in encouraging my paltry attempts at fan fiction own forays into more imaginative writing. To maintain a veneer of objectivity, I will refer to him/them as Pistelli in the body of the text and as John in the footnotes. I will also attempt to restrict any spoilers, wilful misreadings and unnecessary digressions to the notes.

Empirically, however, it seems the question of suicide is rarely resolved philosophically. Emile Cioran, author of such life-affirming works as The Trouble with Being Born, lived to the ripe old age of 84; Sylvia Plath, hardly unread in Nietszche, called it quits at 30.

Meanwhile, our greatest living philosopoher continues to be disappointed in the unsocratic attitudes of the demos.

Fortunately, John is no philosopher.

I have in mind Murdoch’s distinction between fantasy and imagination (from The Sublime and the Good):

Fantasy, the enemy of art, is the enemy of true imagination: Love, an exercise of the imagination […] Freedom is exercised in the confrontation by each other, in the context of imaginative understanding, of two irreducibly dissimilar individuals. Love is the imaginative recognition of, that is respect for, this otherness.

Or does he?

You might have got a bit carried away there, John.

The first and final chapters are appropriately numbered zero and infinity, like a classic tarot deck. I have tried and failed to discern any further numerological significance in the remaining forty-eight chapters.

Future poet-historians will perhaps rhapsodise that John’s decision not to join Twitter was a pivotal moment in the preservation of Western civilisation.

What the kids call a ‘reverse date’.

Mencius Moldbug, eat your heart out.

Since I used to blog under that name, let me play devil’s advocate for a bit.

Nothing in the novel, not the interesting conversations about art, not the making of art, not the repeated exhortations to read Shakespeare and Austen — and certainly not the senseless human sacrifice of Jacob Morrow (not so edifying in real life, is it?) — can redeem the repeated rape of Valerie Karns. The following is the clearest image of truth in the novel:

Simon Magnus wrote a two-page spread that showed, non-sequentially, a cascade of sodomy: The Fool’s father doing to the young Fool what The Fool would go on to do to Sparrow, and the father’s father doing the same, and the father’s father’s father, until he was ordering the artist to draw buggery in Pilgrim times. This Ellen Chandler and Frank Donofrio might have countenanced, but Simon Magnus also wanted to show the grown-up Sparrow assaulting his own young son, and that son assaulting his son, and on into the future, until we were to see sodomy on the rings of Saturn a million years hence, all of this shuffled and disordered, the Pilgrim abutting the alien, like a Tarot pack.

Everything else is just pseudochristian cope.

For a person without gender, Simon Magnus’s treatment of Simon Magnus’s muses is suspiciously reminiscent of that of a stereotypical male artist.

One may wonder whether we really need another retelling of Faust, but this is evidently one of those lessons that humanity is incapable of learning. I can’t resist referring again to Murdoch’s famous description in The Sea, The Sea, which John has also highlighted:

All spirituality tends to degenerate into magic, and the use of magic has an automatic nemesis even when the mind has been purified of grosser habits. White magic is black magic. And a less than perfect meddling in the spiritual world can breed monsters for other people. Demons used for good can hang around and make mischief afterwards. The last achievement is the absolute surrender of magic itself, the end of what you call superstition. Yet how does it happen? Goodness is giving up power and acting upon the world negatively. The good are unimaginable.

But John attempts to do one better than Murdoch. Due perhaps to her strong commitment to moral realism, Murdoch discusses magic but rarely depicts it (apart from vague apparitions like the sea monster that may or may not be an acid flashback). John, on the other hand, relishes the chance to imagine an apocalyptic vision sponsored by MKULTRA 3000.

John appears to share Jung’s belief that we cannot simply dismiss the forces of unreason as products of folk tales and superstitions that the New Man will someday outgrow. Nor should we succumb uncritically to their dark embrace. We need to work creatively to integrate them into our understanding of the world and of ourselves. But such an undertaking is not without peril. The Hölderlin dictum that Jung liked to quote (Wo aber Gefahr ist, wächst das Rettende auch) is also true in reverse. The way up is also the way down.

John says in the Preface that it was done to avoid copyright infringement, but I like my explanation better.

I have to confess that I have never read a comic book or a graphic novel apart from Asterix. And I did enjoy the imaginative retelling of the American industry’s origin in Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay when I read it in high school, a sentiment which John does not share.

John has written on Tumblr something to the effect that race is ultimately superficial compared to the cosmic forces of sex and gender. My character A would say that it is typical of a white man to use a pseudoscientific concept such as ‘cosmic forces’ to justify ignoring the lived experiences of actually existing people here on earth. Artistically though, I think it was a wise choice to not to grab hold of too many live wires at once.

A few observation as someone who has never questioned my gender identity as such but who did once buy a THEY|THEM shirt in the giftshop of the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam because of the Whitmanesque implications (I may have been stoned), only to give up wearing it because it was too awkward to try and explain that I was not trying to make any claims about my particular identity. Hopefully John will have more success in this vein.

I see the shift from sexual politics to gender politics as of a piece with the more general move away from viewing ourselves as relational beings to a more self-contained approach to understanding our place in the world. Although many progressives still parrot the phrase that gender is a social construct, everybody seems to be fretting about whether there is something essential about one’s gender identity — something perhaps even more essential than one’s sex. John’s female characters are rather sceptical about this proposition:

“We’re really not supposed to be saying ‘he,’” Ellen Chandler said. “Simon says he’s not a man or a woman.”

Diane del Greco thought about this proposition for a moment. Finally, with a theatrical scratch of her Caesarian scar, she said, “Give me a fucking break!”

She cackled with laughter. This time Ellen Chandler couldn’t help but join her, seized by a fit of laughter that went with the general delirium she was suffering in this overheated house, inside her long coat, where she felt she was being smothered and berated, the coffee burning her empty stomach and making her dizzy. She felt as if her own Caesarian scar were glowing, burning.

My own perspective is that this particular framing of the issue is regrettable, although not inevitable. What I found to be the most useful explanation in The Identity Trap by Yascha Mounk (himself no stranger to sexual politics) was not the predictable invocation of Foucault’s postmodernism or Crenshaw’s intersectionality but rather Spivak’s ‘strategic essentialism’ (which she herself has largely recanted).

It seems to me that the ‘strategic’ part has all but been forgotten. Whereas the ‘born this way’ narrative was successful in promoting greater social acceptance of homosexuality (at least in the West), it has evidently been counterproductive in the case of transgenderism. It is one thing to convince the average person that a little boy was born destined to like other boys, it is quite another to say that the little boy has actually always been a little girl, or has actually always been neither boy nor girl, in some unique way, somewhere inside her/their problematic boy body. And yet activists have refused to change tack — choosing to shame any questioning of this metaphysically dubious proposition, contributing to the politicisation of the issue in a way that has made gender more, and not less, salient in our interaction with others.

Major Arcana is not the last word on gender. But in its gleeful rejection of standpoint theory it demonstrates that, although we may each be trapped inside our own subjectivity, we can and should try to imaginatively put ourselves in the shoes of others, whatever the gender.

And Simone Weil, for that matter.

John has already anticipated criticism that his ending is a bit pat by saying he was ‘not going to ask people to read a 160K-word novel that leaves them feeling worse about the world than when they started’.

But does this exhilarating 160K-word novel really make one feel better about the world? About the war in Gaza? Should we be satisfied with the answer given to Job? The novel’s metaphysics turn out to be rather familiar: Ye shall be as gods… thou shalt not suffer a witch to live… behold, a virgin shall be with child… greater love hath no man than this… I agree that the likes of Crowley have led us down a blind alley and we have to in a sense go backwards before we can hope to go forwards. But the novel leaves unanswered the question of whether there is a way forward, beyond an imaginative retelling of Judeo-Christian myths. Blake might not have needed the Greeks, but we do. But perhaps this will become clear in the pink utopia.

Thank you! It’s a work that deserves a closer reading yet - so many other threads that I wanted to pick up on, but it risked turning into a thesis!

I can't thank you enough—I have never been read so closely in my life. This would be a great book review even if it weren't about my book: a seamless braid of ekphrasis, appreciation, and critique.

Re: the latter, I won't succumb to the temptation to reply to any real or hypothetical "hostile critic," but I will say I agree entirely with your devil's advocacy.