All right babes, she’s entering her organised era. I decided to put some structure to my writing life by starting a weekly newsletter with the following items on the standing agenda:

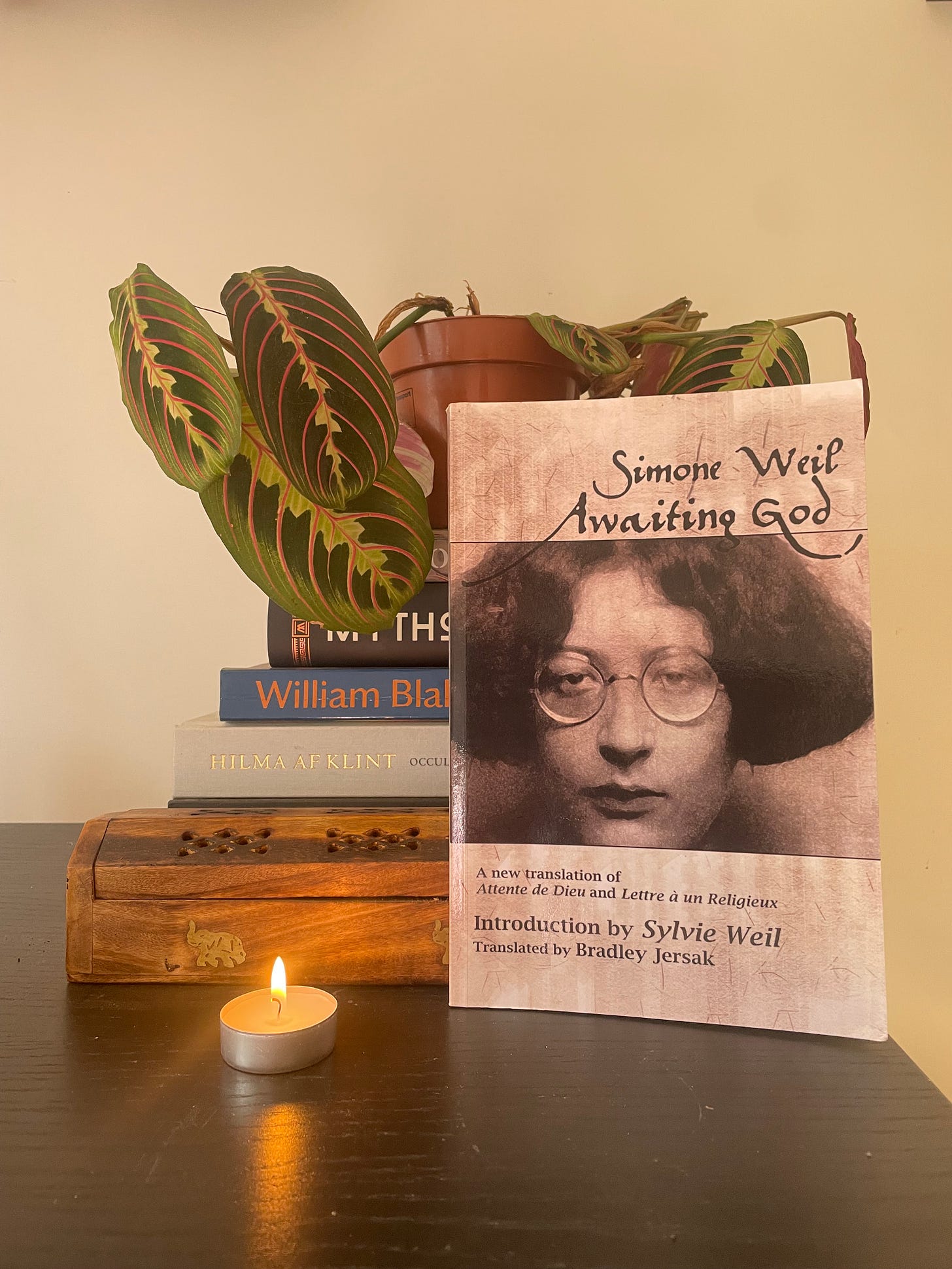

Reflections on Simone Weil

Reflections on Iris Murdoch

Any other business

In this inaugural edition, I will explain how I became obsessed with these two writers and why I think their work is rich enough to revisit week after week. The other business section is for what ever else catches my fancy.

Why Weil?

I’m pretty sure I discovered Weil through Alan Watts.1 I was in my mid twenties and recently free from a problematic long-distance open relationship. I was, one could say, in a spiritually vulnerable place. I listened incessantly to an audio rendition of Awaiting God (read by Rosemary Benson with just the right mix of froideur and tenderness) while walking dazed and confused through the streets of Joburg. I was gripped by images like these:

The beauty of the world is the mouth of the labyrinth. Having entered, the unwary ones take a few steps and in a little while are unable to find the opening again. Exhausted, without anything to eat or to drink, in the dark, separated from kin, from everything they love, from everything they know, they walk without any knowledge, any experience, incapable of even discovering whether they are truly walking or just turning around in once place. But this affliction is nothing compared to the danger that menaces them. For if they do not lose courage, they will continue walking, and it is completely certain that they will finally arrive at the centre of the labyrinth. And there, God is waiting to eat them! Later they will emerge, changed. Having been eaten and digested by God they become ‘other’. After that they will be held at the opening of the labyrinth, gently pushing in others who approach.

I was seduced but also intimidated by Weil. I was afraid to criticise her even for her more ludicrous pronouncements—I thought pointing out her flagrant anti-Semitism completely missed the point. Lately, though, I’ve been wondering how clearly I understood the point, if there is one.

I’m finding My Weil, a recent philosophical novel by Lars Iyer, to be a difficult, at times almost painful, read—even though it is also often hilarious. Iyer asks whether Weil’s message, for all its hopeful talk about waiting on God’s love, merely puts a neoplatonic gloss on the old gnostic hatred of the world as it actually exists. I hope to consider this insightful work in more detail in future instalments of the newsletter.

So it’s not just me. Weil continues to inspire popes and anorexic podcasters alike.2 Susan Sontag provided an intriguing explanation of Weil’s ongoing appeal in a short eponymous essay written in 1963:3

The culture-heroes of our liberal bourgeois civilization are anti-liberal and anti-bourgeois; they are writers who are repetitive, obsessive and impolite, who impress by force—not simply by their tone of personal authority and by their intellectual ardor, but by the sense of acute personal and intellectual extremity. The bigots, the hysterics, the destroyers of the self—these are the writers who bear witness to the fearful polite time in which we live. Mostly it is a matter of tone: it is hardly possible to give credence to ideas uttered in the impersonal tones of sanity. There are certain eras which are too complex, too deafened by contradictory historical and intellectual experiences, to hear the voice of sanity. Sanity becomes compromise, evasion, a lie.

Ours is an age which consciously pursues health, and yet only believes in the reality of sickness. The truths we respect are those born of affliction. We measure truth in terms of the cost to the writer in suffering—rather than by the standard of an objective truth to which a writer’s word correspond. Each of our truths must have a martyr.

In the coming weeks, I will aim to pay careful, yet critical, attention to Weil.

Why Murdoch?

My interest in Murdoch was piqued by pieces like this, but it was these two quotations shared by the indispensable LM Sacasas that prompted me to read her three most famous philosophical essays — The Idea of Perfection, On ‘God’ and ‘Good’ and The Sovereignty of Good:

I have used the word ‘attention’, which I borrow from Simone Weil, to express the idea of a just and loving gaze directed upon an individual reality. I believe this to be the characteristic and proper mark of the active moral agent.

In particular situations ‘reality’ as that which is revealed to the patient eye of love is an idea entirely comprehensible to the ordinary person.

Since then, I’ve dipped in and out of her philosophical work, read five and a half of her twenty-seven novels, became an avid listener of the Iris Murdoch Society podcast, and borrowed the title for my Substack from her famous line:

Love is the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real.

For those unfamiliar with Murdoch, I offer as a further taster one of my favourite passages from The Sea, The Sea:4

‘All spirituality tends to degenerate into magic, and the use of magic has an automatic nemesis even when the mind has been purified of grosser habits. White magic is black magic. And a less than perfect meddling in the spiritual world can breed monsters for other people. Demons used for good can hang around and make mischief afterwards. The last achievement is the absolute surrender of magic itself, the end of what you call superstition. Yet how does it happen? Goodness is giving up power and acting upon the world negatively. The good are unimaginable.’

While reading Weil can be an ecstatic experience, full of deep insights into the nature of the human predicament, she often leaves me dumbfounded as to how to apply these insights in practice. Murdoch manages to refract Weil’s moral vision through the substance of everyday life.

Other business

After I wrote about Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s public declaration of faith, I listened to this conversation between Louise Perry and the evangelist Glen Scrivener. Louise is a sharp thinker and is worth paying attention to, but her religious-but-not-spiritual stance (go to church but don’t think too hard about what Jesus would do about refugees) did not allay my fears about some of the darker motivations behind the neoconservative turn towards cultural Christianity.

I thoroughly enjoyed Blake Smith’s deliciously scabrous tale of The Pride Flag (vs the Church Gays): “people should speak about God and religion if not with reverence than at least with embarrassment”.5

Finally, the inimitable Sam Kriss.

And I’m pretty sure I discovered Watts through a YouTube search for “trippy videos”.

Yes, this is a Red Scare reference.

John Pistelli, a worthy heir to Sontag, makes a related point in a different context, at the start of his review of Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man:

For the good democrat, it’s an unpleasant fact: the best minds are often those least able to reconcile themselves to liberalism. We know the roll-call of great modern thinkers and artists, whether of the extreme right or the extreme left, who held liberalism in contempt and sought to build some utopia beyond it. Nietzsche and Shaw, Pound and Eliot, Yeats and Heidegger, Sartre and Lukács—allowing for the wide divergences among their perspectives, all condemned liberal civilization as an unheroic affair where cunning mediocrities lorded mere wealth and a spurious notion of universal equality over their moral or intellectual superiors. While the good democrat might be tempted to expel these fascist, theocratic, or totalitarian voices from the canon, the strongest version of liberalism might rather be the one that assimilates their critique and answers their challenge.

Unsurprisingly, John Pistelli also quotes this passage in his review of the novel. My faith in John’s judgement was confirmed when he called The Sea, The Sea the culmination of the English novel in an episode of the Grand Podcast Abyss he recorded with his trusty sidekick Sam Worthington. It seems the critical portion of the podcast is currently on hiatus while John is writing his serialised novel Major Arcana (to which you should subscribe), but the back catalogue is well worth checking out.

Please ignore the overenthusiastic comment I left at the bottom. I don’t know what spirit came over me.

Hi, and apologies for the random comment on an 18-month-old post, but I recently read the Lars Iyer book mentioned in this post (picked almost literally at random off the shelves at my local library lol), and am curious if you ever wrote more about it in a way that the Substack search function can't handle lol.

FWIW my take on the novel was "I hope the apocalypse DOES come, just to shut all these miserable losers up" -- but perhaps deeper initiation into the world of Weil would grant me more insight into what the book was going for??

Am ambivalent about Weil, as you probably know, and for the gnostic reason, though I haven't read a lot of her and I do love the Iliad essay. I didn't know that Iyer book existed. I remember him from the radical blog days in the mid-2000s but I never read his fiction back then; he was deep in Bernhard and Blanchot and all that Euro-miserable stuff I could never get into, but My Weil sounds more like something I might read, almost like a grittier Iris Murdoch novel...