Christ loves that we prefer the truth to him, because before being the Christ he is the Truth. If someone takes a detour from him to go towards the truth, they will not go a long way without falling into his arms.

— Simone Weil, Spiritual Autobiography (trans. Bradley Jersak)

The truth is rarely pure and never simple

— Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest

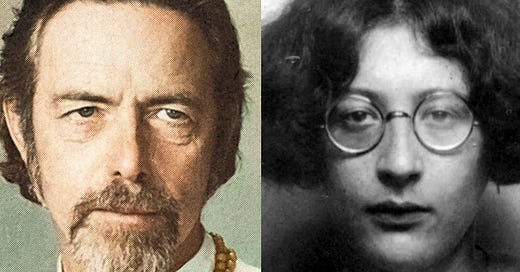

A cynical response to my idea for a Church of Jesus Christ and Mushrooms might be: Typical! It’s like the 70’s Jesus movement all over again! Just another burnt-out hippy yearning for the warm embrace of a personal Saviour. Let me assure you that I am quite aware of this history, which is why I would like to make an unfashionable attempt at learning from it.1 Thus the icon I propose is not a man with flowing hair and a mellifluous voice, but a stone cold butch:

He might have been my first spiritual love, but over time I’ve grown a little disenchanted with the beaded Jesus. I’ve come to realise that if you strip away the Orientalist ornamentation,2 Watts’s message can perhaps best be summarised by the following lines from As You Like It:

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

It’s all a game — so don’t take it so seriously! The connection between this moment and the next moment is purely illusionary! The memories you have of previous parts that you have played and the dreams and fears about future parts that you might play are all just figments of your imagination. All you have is the here and now.3

Watts (who was awarded a master's degree in theology by an Episcopal seminary after his Zen training in New York, but before heading to California)4, often quoted from the sixth chapter of the Book of Matthew:

25 Therefore I say unto you, Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment?

26 Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they?

27 Which of you by taking thought can add one cubit unto his stature?

28 And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin:

29 And yet I say unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.

Watts always referred to himself as a philosophical entertainer rather than a philosopher. His anti-guru stance is probably why he is one of the last gurus standing. Just the other day I saw a Note quoting from The Wisdom of Insecurity:

If we are to have intense pleasures, we must also be liable to intense pains. The pleasure we love, and the pain we hate, but it seems impossible to have the former without the latter.

Alas, towards the end of his life, Watts increasingly turned to the European’s old, unenlightened remedy for numbing the pain of his expanded awareness.

In all my preternatural perambulations as a spiritual seeker (or, less flatteringly, a spiritual junkie), I have, no jokes, not come across a mantra with more practical significance than the following:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

the courage to change the things I can,

and the wisdom to know the difference.5

I fear that beneath the epiphenomena of what some have called the New Paganism (astrology, tarot, spells, etc, none of it particularly new), lies a modernist Buddhist acceptance of the world as it is that can be difficult to distinguish from resignation. As a I responded to

‘s insightful post on Herman Hesse:I read Hesse at a time of my life when I was very disillusioned with politics and the idea of finding fulfilment through an inward journey sounded very appealing. Since then it's been a long, painful realisation that going inward is in a sense taking the easy way out and not confronting the messiness of the external world.

But perhaps the problem lies not with Hesse, but with how we read him: as art of cure rather than art of diagnosis6. Take, for example, this passage from Siddhartha which I highlighted enthusiastically many years ago:

He looked around, as if he was seeing the world for the first time. Beautiful was the world, colourful was the world, strange and mysterious was the world! Here was blue, here was yellow, here was green, the sky and the river flowed, the forest and the mountains were rigid, all of it was beautiful, all of it was mysterious and magical, and in its midst was he, Siddhartha, the awakening one, on the path to himself.

The resonance with the following passage from Madame Bovary is perhaps no coincide:

Ce n’était pas la première fois qu’ils apercevaient des arbres, du ciel bleu, du gazon, qu’ils entendaient l’eau couler et la brise soufflant dans le feuillage ; mais ils n’avaient sans doute jamais admiré tout cela, comme si la nature n’existait pas auparavant, ou qu’elle n’eût commencé à être belle que depuis l’assouvissance de leurs désirs.

Reading Siddhartha as a guide to spiritual refinement is like reading Madame Bovary as a manual for ethical non-monogamy. A spiritual awakening can indeed feel like falling in love with the world again — and who doesn’t like falling in love? But with love comes pain and that is always the hardest part to accept. Unlike Buddhism, Christianity doesn’t promise an end to suffering through mind tricks7, but encourages an acceptance of suffering in the imitation of Christ. The Cross is the enduring symbol: what comes afterwards remains a mystery.8

My more political friends prefer Angela Davis’s radical reformulation: “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.” They see no need for wisdom. The mere existence of injustice implies that the injustice should — and therefore can — be remedied.

In her 1970 essay Existentialists and Mystics, Murdoch too expressed the hope that the political might come to play the role the religious once did in feeding and supporting moral philosophy: she hoped (rather naively, in hindsight) that televised images of “famine in India or war in Africa” would be sufficient to sustain serious moral thinking. Her faith in the salvific potential of politics was short-lived, however: by the 80s she was writing Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals9 and supporting Thatcher.

I confess I’ve not read the whole of Weil’s The Need for Roots (L’enracinement), because I think she says all that needs to be said in the first paragraph:

The concept of obligations takes precedence over that of rights, which are subordinate and relative to it. A right is not effective on its own, but solely in relation to the obligation to which it corresponds. The successful fulfilment of a right comes not from the person who possesses it, but from others who recognize that they have an obligation towards that person. The obligation takes effect once it is recognized. If an obligation is not recognized by anyone, it loses nothing of the plenitude of its being. But a right that is not recognized by anyone amounts to very little.

Our cherished human rights mean nothing if humans do not recognise their obligations towards each other. In the West, the task of encouraging people to accept these obligations has largely shifted from religious to secular institutions. But secular education has hardly been successful in this endeavour: not only has it failed to cultivate a society of moral philosophers, it has failed to produce a cadre of them that society can turn to for ethical guidance (unless one wants to cite an ethicist as an expert to further one’s political cause): moral philosophy has become just one more academic discipline which those on the outside suspect is a bit of a joke.

That’s why, however personally tempting, I am wary of Brother Lin’s prescription to leave society: I worry that soon there will be nobody left in society.10 Society is a Mechanical Turk — and the Turk has absconded!

If I really believe that the important thing is being part of a moral community, why don’t I just go to church, instead of indulging my poorly digested Messiah complex and hereditary sectarianism in what at least one of my readers has described as “mental masturbation masquerading as pseudo-intellectualism”? Is a spot of hypocrisy not a fair price to pay?

Call me obstinate, but since my adolescence I have clung to the following counsel from Vaclav Havel: “Keep the company of those who seek the truth — run from those who have found it.” Weil explained her refusal to be baptised in the Catholic Church with reference to two words: Anathema sit — the traditional formula for excommunicating heretics.11 As Freud remarked wryly in Civilisation and its Discontents: “After St Paul had made universal brotherly love the foundation of his Christian community, the extreme intolerance of Christianity towards those left outside it was an inevitable consequence.”

That’s why I remain hopeful that Murdoch’s development of Weil’s ideas can point us in the right direction. In my humble opinion, the three philosophical essays collected in The Sovereignty of Good succeed in severing Christian moral philosophy from Christian dogmatism (and in modernising Platonism, which is perhaps the same thing). As she writes in On ‘God’ and ‘Good’:

Morality has always been connected with religion and religion with mysticism. The disappearance of the middle term leaves morality in a situation which is certainly more difficult but essentially the same. The background to morals is properly some sort of mysticism, if by this is meant a non-dogmatic essentially unformulated faith in the reality of the Good, occasionally connected with experience. The virtuous peasant knows, and I believe he will go on knowing, in spite of the removal or modification of the theological apparatus, although what he knows he might be at a loss to say.12

Like the Russian revolutionaries learned from the French revolution?

This is not exactly fair — if you’re looking for an entertaining introduction to Eastern philosophy (and, more covertly, Western esotericism), you could do worse than Watts!

For those of you still fighting the good fight and keeping tabs on MK-ULTRA, do you think the 70’s Jesus movement was a coincidence? And one day all of these Jesus people suddenly decided to double-time Mr Nice Guy with Daddy Trump (a Golden Calf if I’ve ever seen one)? Since heterosexual men have been cancelled, the deep state can no longer rely on a metaphysical Lothario like Watts to lure the sheeple into a false sense of security, but luckily for them, there are plenty of queens and mothers and non-binary legends that will do the trick.

This is of course The Serenity Prayer, attributed to the Protestant theologian Richard Niebuhr, and popularised by Alcoholics Anonymous, whose co-founders Bill Wilson and Bob Smith had met at a meeting of the Evangelical Oxford Group. Which is why I found it funny when Sam Kahn compared the spirit of AA to that of medieval Catholicism!

I find it striking that Gribbin readily offers examples of artists of diagnosis: Coetzee, Michaux, Tamura Ryuichi, Celan and Marlene Dumas (two South Africans!), but in illustrating the art of cure she refers not to art, but nature: “The cult of beauty is the hygiene, it is the sun, air, and the sea, and high-quality animal protein and good sex.”

This is probably an unfair characterisation of Buddhism — I don’t wish to offend Buddhists any more than Christians.

The oldest version of the Gospel of Mark ends abruptly with the sight of the empty tomb.

Which I am yet to grapple with.

Brother Lin has not left society complete, his stream of Notes on this very platform is an invaluable fount of wisdom.

The butt-hurt right (those who like to refer to the liberal establishment as the Cathedral) has predictably reacted to the new way of saying “Anathema sit”, “You’re just weird”, by either going “I’m not weird, you’re the one that’s weird!” or “I’m proud to be weird!”

I’ve got no problem with weird. Humping a couch is weird. Endorsing dehumanisation is evil.

Although a little earlier in the essay, Murdoch admits that she is “often more than half persuaded” to think in the following terms:

Perhaps indeed all is vanity, all is vanity, and there is no respectable intellectual way of protecting people from despair. The world just is hopelessly evil and should you, who speak of realism, not go all the way towards being realistic about it?

Sometimes the truth lies in the disagreement.

It's kind of crazy Murdoch ends up being a Platonist in the modern world. I'm hard pressed to explain why though.

This is so excellent, Mary Jane. And thank you for making me a footnote!

I have, I will admit, also found myself struggling to reconcile Alan Watts' (richly stentorian) refrain that "life is a dance" with his succumbing to "the unenlightened remedy," as you put it.

As before, just a dizzying array of thinkers and syntheses here. You've succeeded in stoking an inchoate interest in Weil as well.